November is an important month of remembrance for Catholics and the Church. It starts with the solemnity of All Saints followed, on the next day, by ‘The Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed’ – or All Souls as we call it. In many countries families visit graveyards and cemeteries in order to pray for and adorn family graves with votive candles, flowers, pictures and incense. Polish cemeteries are a sight to behold, often described as a ‘sea of light’ to remember the dead.

At the eleventh hour on the eleventh day of the eleventh month, we remember the fallen of our wars. The Armistice, an agreement that ended the fighting of the First World War ahead of peace negotiations, began at 11am on 11 November 1918. Armistice is Latin for to stand (still) arms. We also pay our respects to the Armed Forces family on Remembrance Sunday.

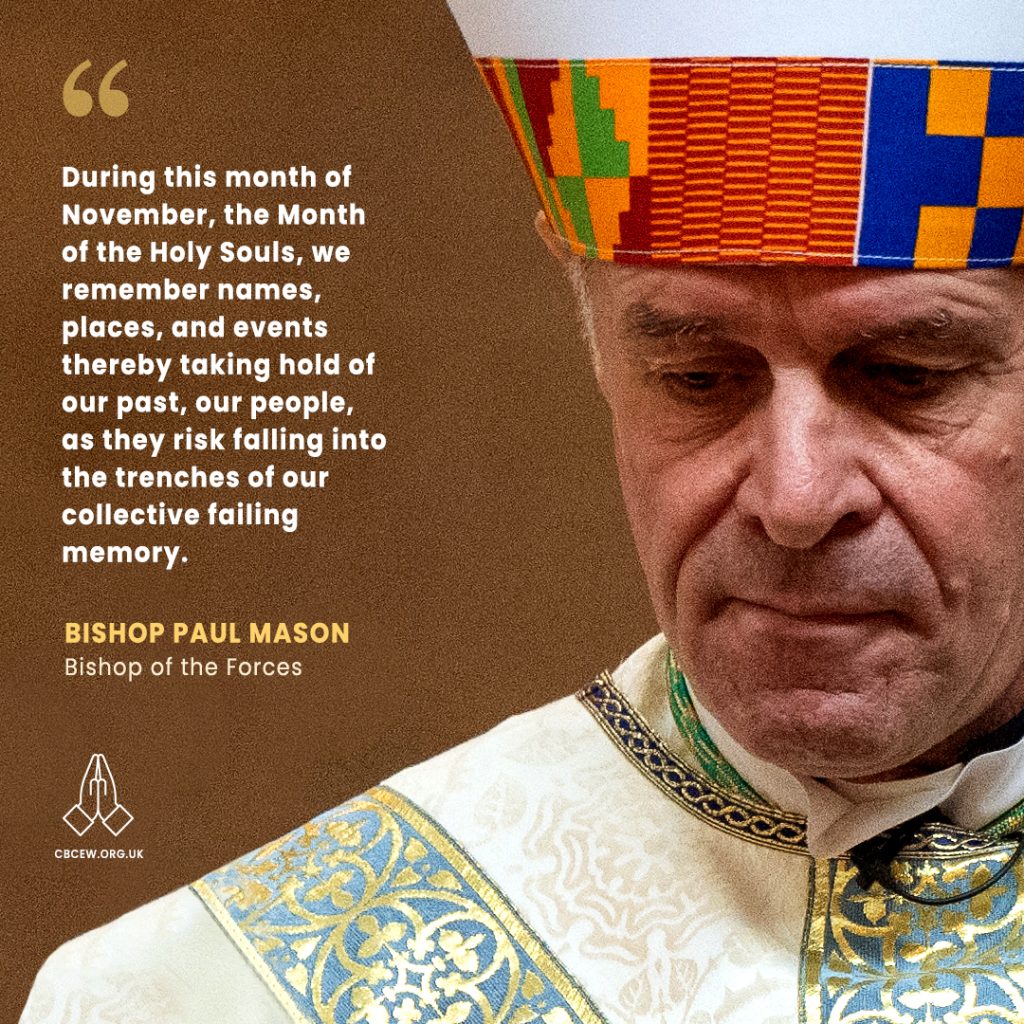

Bishop Paul Mason is the Catholic Bishop of the Forces. He offers this reflection to help us focus on the fallen who sacrificed so much for the freedoms we enjoy today.

The difference between a myth and a historical account can be seen in the telling: the former usually takes the form “once upon a time” and then proceeds to highlight some generalised truth of the human condition; the latter gives details such as time, place, person and event. Although both offer valuable insights, care should be taken not to conflate them. Hercules is no more historic than Winston Churchill is mythic. Mythologising people from our past simply serves to set them apart as disembodied ideas separate from our own lived and concrete experience. Our Christian history is not immune to this tendency either with those who would reduce Jesus himself to an archetype, expounding common truths like other wise teachers of the past. Remembering names, dates, places, and events helps us to ensure this does not happen. It maintains our solidarity with the past.

All of those who served in the Great War have now died and so remembering them becomes increasingly important. They may be known only unto God, but they are our brothers and sisters as well. The National Memorial Arboretum helps us remember, and does so with much dignity, as do British military cemeteries throughout the world.

One small constituency we may not immediately call to mind, however, is that of military chaplains. In the First World War 179 paid the ultimate price, 36 of whom were Catholic, including Fr Willie Doyle whose cause for canonisation is still proceeding and, please God, will serve as a beacon of priestly heroism.

For our part at the Bishopric of the Forces we have had three books written on the history of Catholic chaplaincy in the Armed forces by historian James Hagerty. These go a long way to ensuring brave Catholic priests and the contribution of the Church to the nation are nor forgotten and are not reduced to fireside tales.

During this month of November, the Month of the Holy Souls, we remember names, places, events thereby taking hold of our past, our people, as they risk falling into the trenches of our collective failing memory. The historian Arthur Toynbee described some approaches to history as being nothing more than “just one damn thing after another”. When we lose sight of the raw details, the humanity, the suffering and sacrifice then our fallen become one damn soldier after another, one damn chaplain after another. There is a bond of trust between the living and the dead and if ye break faith with those who died, we shall not sleep.

Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord,

and let perpetual light shine upon them.

May they rest in peace.

Amen.